By the 1870’s Virginians were aware of the great depletion of major food fisheries due to overfishing and multiple dams blocking fish runs. The Virginia Assembly created the office of the Virginia Fish Commissioner in March 1871 to evaluate Virginia’s commercial fisheries and make recommendations for restoration. One of the main strategies was artificial propagation. William Ball was the first fish commissioner of Virginia and focused efforts to propagate and release shad, black bass, and trout. In 1894, the Virginia Commissioner of Fisheries wrote “the question of greatest importance to our fishermen is the appalling decline in the number of the free migratory fishes that annually visit the waters of the State.” (Wilkins 1894). This effort was parallel to efforts in other states as well as the federal government, which established the Commission of Fisheries in 1871, to examine depletion of fisheries in the nation. Seth Green, the father of fish culture, opened the Caledonia Hatchery in 1864 and the race to build hatcheries was on. The first hatcheries in Virginia did not raise shad or striped bass. First hatcheries to propagate these fishes were at Fort Washington and Fishing Battery Island (Maryland) and Albemarle Sound at Edenton, North Carolina.

|

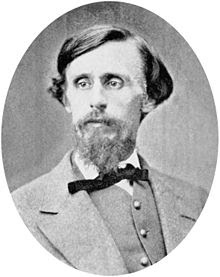

| Marshall McDonald was Virginia Fish Commissioner 1875-1888 and U.S. Commissioner of Fish and Fisheries from 1888 to 1895. Photo Source. |

|

| McDonald Fishway with Water Shut Off, in Great Falls of the Potomac, 1898. Public Domain. |

Marshall McDonald traveled to Wytheville, Virginia in August, 1879 to select a location for a fish hatchery. This new trout hatchery was built on 3 ½ acres of land donated by S.P. Browning (Chitwood 1989). The location 3.5 miles west of Wytheville, off Old Stage Road, was ideal with two springs that produced 1,100 gallons per minute and was directly on the Atlantic, Mississippi and Ohio Railroad line (later Norfolk & Western). It was in operation by November and was operated by the U.S. Fish Commission in 1882 and completed in 1888. At the time there were twelve rearing ponds for trout, piping to ponds, a retaining wall on Tate’s Run, and a two-story building for rearing troughs. The Wytheville hatchery raised the McCloud strain of Rainbow Trout from eggs shipped from the federal hatchery on the McCloud River.

|

| Wytheville hatchery layout circa 1886. (McDonald 1889). |

|

| Water supply and brood fish ponds at Wytheville hatchery, circa 1886. |

From annual reports of the U.S. Fish Commission we find that “In the spring of 1885 about 300 grayling were hatched from eggs collected from wild fish in the streams of Michigan by Mr. F. N. Clark and forwarded to Wytheville. These 300 fish are being kept for breeders, and at the close of the year were in fine condition.” (U.S. Fish Commissioner. 1887 Page ixxxii). Further, stocking of Rainbow trout to the headwaters of the Shenandoah River in Augusta county and tributaries of Potomac in Maryland as well as ponds in Maryland, SW Virginia and Tennessee occurred in 1886 (U.S. Fish Commissioner. 1887. Page ixxxv)

|

| Hatchery troughs at the Wytheville hatchery, circa 1886. (McDonald 1889). |

|

| Hatchery trout plan view for Wytheville hatchery. (McDonald 1889). |

In the fiscal year ending June 30, 1887, McDonald (1889, p 4-5) reported receiving Rainbow Trout from California, Brook Trout from Michigan, Brown Trout from New York, Atlantic Salmon from Maine, Common Carp from Washington, D.C. and Rock Bass and Smallmouth Bass collected locally from New River and Reed Creek. The Atlantic Salmon were stocked in a tributary of the Shenandoah River near Staunton and South Fork of Shenandoah River near Waynesboro.

The first superintendent of the Wytheville Hatchery was William E. Page of Lynchburg, and he was soon succeeded by George A. Seagle, a native of Wythe County. Seagle invented the Seagle shipping box for transporting trout fry long distances. Seagle was succeeded in 1922 by Charles B. Grater of Leadville, Colorado, who served until 1930. In 1930, Samuel A. “Gus” Scott became the fourth hatchery manager (Chitwood 1989). Under Scott’s management the Wytheville, hatchery produced 20,000 to 25,000 pounds of fish annually, mainly Rainbow Trout, bass, and bream.

|

| Satellite view of hatchery, now operated as Brakens Fish Hatchery. photo (c) Google Maps 2019. |

This historic hatchery operated until 1968, after a new facility was opened on Reed Creek. The hatchery was donated to Wytheville Community College for use in biology classes. In 1987, it was purchased by Dale Bracken who restored the hatchery, which now operates as Brakens Fish Hatchery for recreational fishing.

|

| Brook Trout. Photo by Steve Droter. CC BY-NC-2.0 Source. |

Approximately 100,000 anglers fish for stocked trout in Virginia waters and their fishing satisfaction depends on annual stocking of catchable-size trout. Wild trout occur in over 2,300 miles of coldwater streams in the Commonwealth and native Brook Trout Salvelinus fontinalis thrive only in higher-elevation mountain streams. Five trout hatcheries operate to produce stocked trout in Virginia. These include stations at Marion (Smyth Co.), Montebello (Nelson Co.), Coursey Springs (Bath Co.), Paint Bank (Craig Co.), and Wytheville (Wythe Co.). Trout hatcheries are open to the public to tour and learn more about the propagation of trout. Teachers can connect students to local watersheds with Trout Unlimited's Trout in the Classroom program, which raises trout from egg to the fry stage for stocking.

Chitwood, W.R. 1989. The old Wytheville fish hatchery. The Mountain Laurel the Journal of Mountain Life. September

U.S. Fish Commissioner. 1887. Report of the Commissioner of Fisheries to the Secretary of Commerce and Labor for 1885. U.S. Bureau of Fisheries Washington Government Printing Office 1887.

McDonald, Marshall. United States Commission of Fish and Fisheries. 1889. Report of Operations at the Wytheville Station, Virginia, from January 1, 1885 to June 30, 1887. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office.

McHugh, J.L., and R. S. Bailey. 1957. History of Virginia’s commercial fisheries. The Virginia Journal of Sciences 8(1):42-64.

The Advocate. 2006. Salmon in the Maury? It wasn’t just a fish tale. The Rockbridge Advocate. December 2006. 49-54.

Virginia Fish Commission. 1877. Annual Report of the Fish Commissioner of the State of Virginia.

Wilkins, J.T., Jr. 1894. The Fisheries of the Virginia Coast. In House Misc. Doc., 53rd. Congress, 2nd Session, Vol. 20, Bull, U.S. Fish Comm., for 1893: 355-356. Cited in McHugh and Bailey 1957.