|

| New River between Eggleston and Pembroke, Virginia. Photo by D.J. Orth. |

The New River is one of the world's oldest rivers and it's course was established before the uplift of the Appalachian mountains and dissects those very mountains. New River today flows 320 miles from the source in Ashe County, North Carolina, to the confluence with the Gauley River, Gauley Bridge, West Virginia, where it becomes the Kanawha River. The upper New River drainage was a refugia for coolwater fishes during the Pleistocene glacial advance and now supports eight endemic species of fishes. The erosive force of water, resistant rock formations, and long history combined to create beautiful palisades, natural impassable falls (Kanawha and Sandstone) and many passable falls and rapids that provide numerous opportunities for whitewater enthusiasts.

On May 21, 2016, we recognize World Fish Migration Day in order to enhance awareness of the human connections to rivers and migratory fishes. Although we are frequently reminded of the long migrations of salmon, eel, shad, and striped bass in North American rivers, fish migrations are much more commonplace than previously assumed. Disruption of fish migrations are a world wide concern. In the US, 74,000 dams block the rivers and streams. These structures impede passage of fish, degrade water quality, trap sediments, and reduce river-based recreation and economic opportunities for local communities. Building dams is long-term, irreversible decision, at least in terms of human life spans. The US Fish and Wildlife Service and other federal agencies have programs to promote fish passage around barriers. All dams on the New River were built with no fish passage structures and there are no imminent plans for removal.

Most people divide the New River in three major segments: (1) upper New River above Claytor dam; (2) lower New River from Claytor Dam to West Virginia; (2) New River Gorge from Bluestone dam to the confluence with the Gauley. Moving from the upper New River downstream, the dams include Fields, Fries, Byllesby, Buck, Claytor, Bluestone, and Hawks Nest. None of these structures permit upstream fish passage. Fields Dam is an old woolen mill dam.

|

| Fields Dam, Mouth of Wilson, Virginia. Source Panoramio |

Fries Dam is a 41-foot high, rock masonry dam that was built in 1902 to power a textile mill. Today the textile mill is gone and the project produces hydro power with four turbines. The impoundment is filled with accumulated sediments and average depth is less than 4-6 feet. For a slide show of photos around the Fries Hydroelectric project, click here. Only when flow exceeds the hydraulic capacity of the turbines does water spill over the dam; at these times the water carries a high sediment load. See video of Fries dam spilling.

|

| New River impounded by Fries Dam. Island (upper right) was formed since the Dam was constructed. |

Historically, Walleye

ran through this reach of the river upstream to Fields Dam. Palmer et al.

(2006) contends that the New River supports a unique southern strain and the current Walleye stocking program has increased

abundance and angling effort for Walleye (Palmer et al. 2007). This strain is regionally significant as they

are adapted for riverine spawning and grow to an impressive size (Virginia’s

record was 15 pound, 15 ounces, caught by Anthony P. Duncan in

2000).

Byllesby and Buck Dams are only 2.7 miles apart and were constructed from 2011-2012 in one of the steepest gradient sections of the New River; historical photos are available here. To view a flyover of Byllesby, click here. Each dam is a constructed 44-foot high concrete dam; the two dams operate as one joint hydroelectric project with 30.1 MW capacity. Byllesby-Buck powerhouses are operated by Appalachian Power Company. There are no fish passage facilities and walleye fingerlings must be stocked above Byllesby in order to restore a native walleye population in the reach between Byllesby and Fries dams. Further, there are no minimum releases, other than leakage, in the Buck Dam bypass reach.

Byllesby and Buck Dams are only 2.7 miles apart and were constructed from 2011-2012 in one of the steepest gradient sections of the New River; historical photos are available here. To view a flyover of Byllesby, click here. Each dam is a constructed 44-foot high concrete dam; the two dams operate as one joint hydroelectric project with 30.1 MW capacity. Byllesby-Buck powerhouses are operated by Appalachian Power Company. There are no fish passage facilities and walleye fingerlings must be stocked above Byllesby in order to restore a native walleye population in the reach between Byllesby and Fries dams. Further, there are no minimum releases, other than leakage, in the Buck Dam bypass reach.

|

| Buck Dam with no minimum flow release. Source |

Claytor Dam is 137-foot high concrete dam built by Appalachian Power Company in 1938. The Claytor Hydroelectric project has four generating unit with a total capacity of 75 MW. It began operation in 1943 under a license from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. Claytor Lake is a 4,363 acre lake impounded by the dam and provides numerous water-based opportunities along its 21-mile length. Fish cannot pass upstream though some downstream passage does occur.

|

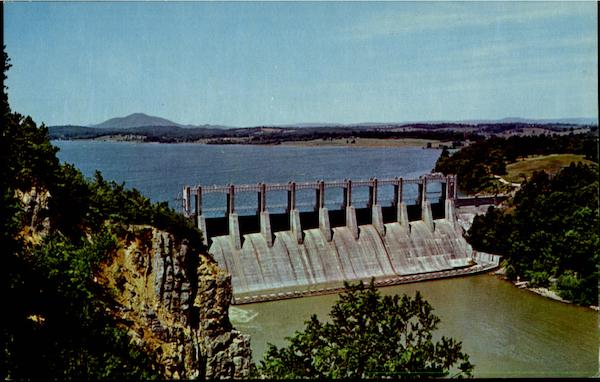

| Claytor Dam Source CardCow.com |

Bluestone

dam, near Hinton, West Virginia, impounds a 10.7 mile stretch of the river, creating Bluestone Lake, a flood control impoundment. During times of flooding the river backs up to the Virginia line. Construction of the dam began in 1941and, due to suspension of work during world war II, it was not completed until 1949. There are no fish passage structures on the Bluestone Dam.

|

| Bluestone Dam Source |

Hawks Nest Dam was completed in 1933. It created a 250-acre lake and during much of the year all river flow is diverted through a tunnel to power a metals plant at Alloy, West Virginia. The diversion creates a 5-mile reach called "the Dries" that consists of large bedrock and boulders amidst a frequently dewatered river. The tunnel construction began in 1930 and was one of the worst occupational disasters in US history. Over 700 mostly black, mostly migrant workers died from acute silicosis from work in the tunnel (Chermiack 1986).

Eight endemic species of fish live in the upper New River; these include the Appalachia Darter, Bigmouth Chub, Candy Darter, Bluestone Sculpin, Kanawha Darter, Kanawha Minnow, Kanawha Sculpin, and New River Shiner. These and other fishes, such as the Flathead Catfish, Channel Catfish, White Sucker, Northern Hogsucker, Smallmouth Bass, persist in the New River but are unable to migrate very far. They are also blocked from entering large tributaries, such as the Little River and Wolf Creek, due to dams that block passage into these tributary waters.

|

| Hawks Nest Dam. Photo by Duncan. source |

Eight endemic species of fish live in the upper New River; these include the Appalachia Darter, Bigmouth Chub, Candy Darter, Bluestone Sculpin, Kanawha Darter, Kanawha Minnow, Kanawha Sculpin, and New River Shiner. These and other fishes, such as the Flathead Catfish, Channel Catfish, White Sucker, Northern Hogsucker, Smallmouth Bass, persist in the New River but are unable to migrate very far. They are also blocked from entering large tributaries, such as the Little River and Wolf Creek, due to dams that block passage into these tributary waters.

|

| Flathead Catfish are the largest native fish in the New River. Photo by Jason Emmel |

White

sucker and Northern Hogsucker migrate into small, shallow tributaries during spawning, where they are easily observed by local citizens. Walleye in the New River are restricted to movements between Claytor Lake and Buck Dam. The net effect of these barriers to migration is fragmentation of fish populations into smaller, perhaps less viable, units that are less able to move and adapt to future climate changes.

|

| Northern Hogsucker Photo by Ben Cantrell |

|

| Pistolgrip, Quadrula verrucosa, Endangered in Virginia. source |

|

| Fries Dam and dewatered intake canal showing fine sediments filling reservoir and canal. Source p 128. |

Take a moment to remember that fish can't travel like we can. Further, remember that the many fishes, mussels, and crayfishes that make the New River home are blocked from moving into or out of the river fragments. We do not fully understand the long term effects of fragmentation; however, we know that fish have to move in order to adapt to changing climate and thermal regimes. Support local conservation activities in the New River, by joining the New River Conservancy. Explore the many areas of the New River that can be paddled through (Trout 2003). Perhaps, organize an event to link people to the river on or around World Fish Migration Day. Take a river float and enjoy your ability to move along the river! Fish for trophy size Smallmouth Bass and Muskellunge. Plan your trip using access maps available from the National Park Service and Department of Game and Inland Fisheries. Refer to the New River Guide by Bruce Ingram to assist in selecting segments to paddle or fish.

References

Butler,

S.E., and D.H. Wahl. 2011. Distribution,

movements and habitat use of channel catfish in a river with multiple low-head

dams. River Research and Applications

27:1182-1191.

Chermiack, M. 1986. The Hawk's Nest Incident. Yale University Press. 224 pp.

Copeland, J.R., D.J. Orth and G.C. Palmer.

2006. Smallmouth bass management in the New River, Virginia: A case study of

population trends with lessons learned. Proceeding of the Southeastern Association

of Fish and Wildlife Agencies 60:180-187.

Easton, R. S., and D. J. Orth. 1994. Fishes of the main channel New River,

West Virginia. Virginia Journal of

Science 45:265-277.

Ingram, B. 2014. New river guide: paddling and fishing in

North Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia.

Secant Publishing, Salisbury, Maryland.

Palmer, G.C., J. Williams, M. Scott, K.

Finne, N. Johnson, D. Dutton, B.R. Murphy, and E.M. Hallerman. 2007.

Genetic marker-assisted restoration of the presumptive native walleye

fishery in the New River, Virginia and West Virginia. Proceeding of the Southeastern Association of Fish and Wildlife

Agencies 61:17-22.

Trout,

W.E. 2003. The New River atlas: rediscovering the

history of the New and Greenbrier rivers.

Virginia Canals and Navigation Society, Lexington, VA.

Vokoun, J.C., and C.F. Rabeni. 2005. Variation in an annual movement cycle of flathead catfish within and between two Missouri watersheds. North American Journal of Fisheries Management 25:563-572.

Vokoun, J.C., and C.F. Rabeni. 2005. Variation in an annual movement cycle of flathead catfish within and between two Missouri watersheds. North American Journal of Fisheries Management 25:563-572.

Typo stating that the dams were built in 2011-2012 - Should be 1911-1912. Also you link to the "flyover" video for Byllesby is incorrect. That is not the Byllesby dam in Virginia.

ReplyDeleteThe post is written in very a good manner and it contains many useful information for me. stop for travel enthusiasts

ReplyDeletewaterless live fish transport technology A Filipino invented a technology that can transport live fishes

ReplyDelete